Recovering Deleted PS3 Executables: Blur Edition

Preface

In September 2024, I was sent an HDD image from a Bizarre Creations PS3 devkit. This has since been publicly released (or perhaps rereleased; it’s unclear). Several builds had already been recovered by this point, but it was requested that I look over it and attempt recovery of anything that previously proved too difficult to retrieve.

It’s worth noting there are two other images (albeit X360) I haven’t looked at which contain Blur 2 builds. I intend to look at these in the future, but MrPinball64 has already done extensive recovery work on them and it’s my understanding that the same has been requested of several other people. Due to this, I decided to focus on the image that received less attention.

Part 1: Initial efforts

Investigation

As with other kits I’ve encountered, the first—and likely only, at least for a while—order of business was executables. Checking the ones that have already been recovered, there are a few interesting points. For one, and rather unusually, the 2009-12-15 build uses ELFs rather than SELFs. There are also a couple hundred intact smaller ELFs in the dontship folders attached to the 2010-01-11 and 2010-03-19 builds. I made sure to map out the positions of the main executables in the drive before continuing.

Looking through the search results for both SELF and ELF headers and filtering by the size field, it became clear that not much had been left on the table. However, there’s one SELF header at offset 0x40624A000 that doesn’t match up with anything previously recovered. This fragments quite quickly (0x1C000), so just to make sure there’s actual build data instead of going on a wild goose chase, I searched for potential build dates since those are present in the other executables.

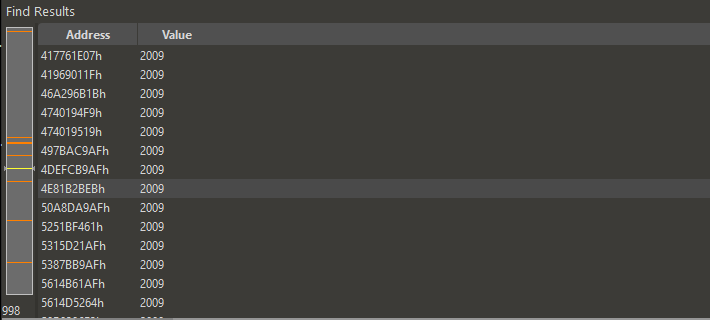

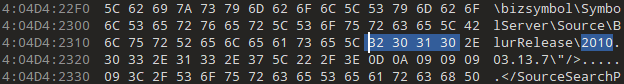

936 of the 988 hits for 2009 are from the one map file remaining on the drive. The remaining 52 are mostly false positives, filesystem-related paths, and results from the already-recovered 2009-12-15 build, but there are a few unknown sections like these:

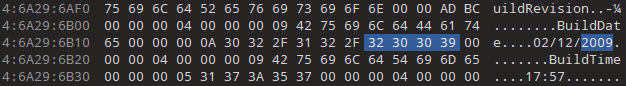

Despite their build dates and such making it seem like they’re from an executable at first glance, it turns out they’re actually the level assets, and all other levels contain a similar plaintext date of creation. This is quite unusual in my experience; normally a FILETIME or time_t would be stored instead. At least this could be useful in asset recovery, but that’s not the focus right now.

Moving on to 2010, there are 260 results. This is skewed by symbols and level files again, but this time there’s something else:

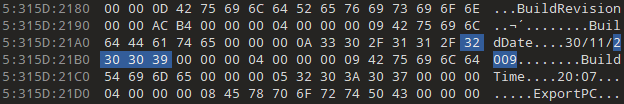

The first two are project files for ProDG Debugger, both for Amax_Speed.self. Similar project files are present in other recovered builds, for 2010.03.19.2 and 2010.01.11.2. This indicates that there were 2010-03-13 and 2010-03-17 executables on here at one point. Not that different from the already-recovered 2010-03-19 build, but any potential executables are worth trying for.

The third result is the most interesting one: executable data for 2010-03-17. It looks like this build is the only one that survived, and if there was more than one configuration then the others are gone. (The configuration should be Speed, but that’ll have to be confirmed later.) That means there’s either one recoverable executable or none, so it’s time to find out whether this data is part of the SELF seen earlier.

Beginning defragmentation

Matching a SELF with its fragments (or vice versa) isn’t always straightforward. Normally, there are multiple executables that need to be filtered through, so there’d be lots of searching and comparing sizes/offsets/data/instructions and determining matches through process of elimination and perhaps trial and error. In this case though, with only one SELF header fragment, one executable data fragment, and a debugger project file supporting there being only one in the first place, it’s relatively safe to assume they go together. If not, that can be verified later. The question is where it goes, and to learn that, the other fragments need to be found.

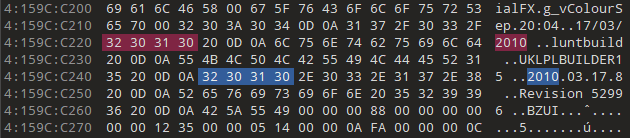

Before searching, it’d help to have a point of comparison from 3/19. Now is the time to verify that the 3/17 configuration is Speed. I used a string that exists in every configuration but master to get the answer:

Based on 3/19, this is exactly where it’s expected to be relative to the build date found earlier, which confirms it’s part of the same fragment and that the whole fragment is from 3/17’s Amax_Speed.self.

Starting with the first fragment and using 3/19 amax_speed.self for comparison, I first checked for unique data from just before the fragment point (0x1C000):

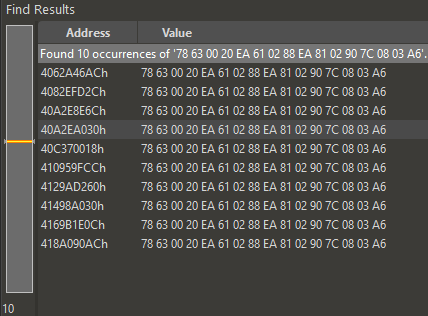

The data in 3/19 is offset by -0x64 compared to 3/17. Searching for data from 0x30 after this yields several results, with expected matches ending in 030:

There it is at 40A... exactly as hoped. Or is it? The first time around, I actually missed that there was a second result at 414... since I hadn’t done a complete scan and assumed there would only be one match, and even if there was another the closest one to the SELF fragment at 406... would make more sense. To save some time writing this, suffice to say I chased the wrong fragment for a long time and 414... was the right one. 40A... is likely part of the now-destroyed 3/13 executable.

At this point I became demoralized and took a break. Which turned into a very long break. And then I came back.

Part 2: Recovering the right thing

More defragmentation

In February 2025, I returned to work on 3/17 recovery. I managed to forget about the earlier debacle but correctly deduced that the 414... fragment was the correct one this time because this time I’d decided to properly check certain parts of the executable, including the SELF/ELF info (possible thanks to some beautiful certified file and SELF/SPRX documentation on psdevwiki). This wasn’t strictly necessary for defragmentation but proved valuable later.

Thanks to the earlier mapping of executable starts, where the start of the 3/19 amax_master.self limited the fragment size, I realized the fragment was either mostly or entirely complete and at first appeared to be one block with a size of 0x200C000. This includes the build date and configuration from earlier, further confirming it. Only problem is, adding the two fragments results in a size of 0x2028000. This on its own isn’t suspect, but from prior experience I knew PS3 files like to be in blocks of length 0x2030000; in other words, this block’s missing 0x8000. It’d be highly unusual for this to occur on its own, so I figured it probably went along with a missing 0x20000 fragment somewhere.

Just to confirm my suspicions, I checked the segment extended headers and compared the size of the first segment with the actual size of the recovered segment. Sure enough, it was supposed to be 0xFD5978 long but was 0xFCD978 instead, a difference of 0x8000.

In the end, I had to figure out a way to know the function locations in 3/17 without having an intact executable so I could compare those locations with what was actually in the file. And luckily, there was a way.

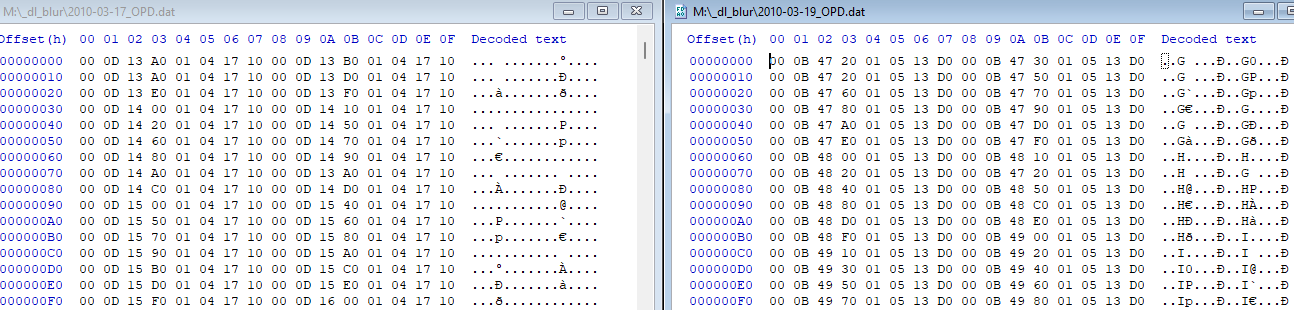

Comparing via .opd

In builds like these, the .opd (official procedure descriptors) section isn’t very interesting under normal circumstances. You can get significantly more info from DWARF debugging symbols. However, by this point I’d searched for the end of the file (where many of the symbols are) and knowing its file size I found that nothing aligned to it, meaning the symbols had been destroyed. Needing function locations, .opd proved the best section to turn to.

By comparing these function locations with analyses of both the 3/19 executable and the broken 3/17 executable in Ghidra, I was able to determine the exact location of the fragmentation. It turned out to be 0x20000—the fragment found previously was a mere 0x4000 long. Worse still, the data after it didn’t seem to exist in the image anymore, but I’ll circle back to that problem later.

Armed with .opd’s function locations and Ghidra, it was possible to figure out what was valid and where it needed to be. I determined there was a 0x28000-wide gap (0x20000 to 0x48000); this extended the total size to the expected amount, 0x2030000, which finally gave me some confidence that the fragment mapping was correct. But now there was a new problem, that of the missing data, and I wasn’t sure it was fixable.

Part 3: Regenerating the code

Remember how in part 1, the assembly in 3/17 and 3/19 was identical but shifted by 0x64? Well, after comparing the data before and after the missing 0x28000, it turns out both parts are offset by that amount, which means the missing middle section is almost certainly identical (or near-identical) between both. Of course, it’s not as easy as copy-pasting, but at least it can be overcome.

Or can it? I hadn’t done this before, and after some searching I can confidently say nobody else had either. In other words, the method of fixing this was purely theoretical. Either way, it was worth a shot.

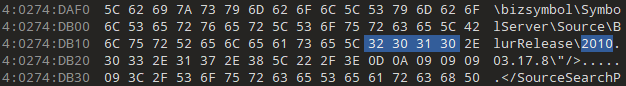

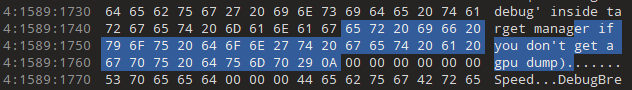

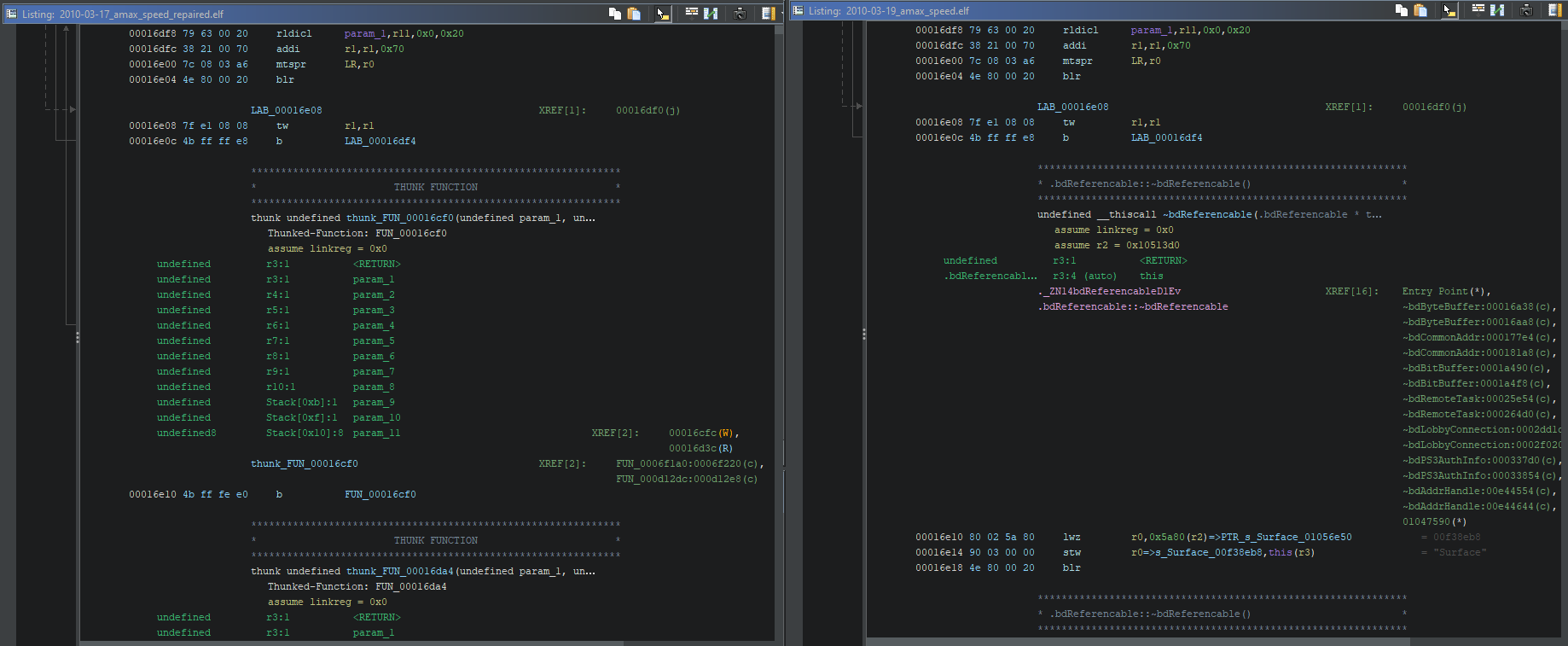

Above is where the two executables diverge. I ended up taking sample data from (offsets are file-relative) 3/17’s 0x7800 and 3/19’s 0x779C with a length of 0x18800, and 3/17’s 0x48000 and 3/19’s 0x47F9C with a length of 0x1714C. I referred to IBM’s PPC instruction set pages and PPC instructions list for what came next.

The sample data proved to be a perfect choice for testing. Using it, I could easily see what would need changing to recreate the missing 3/17 data from 3/19’s data. This effectively ended up being two things:

- The load instructions (

lwz,lhz,lbz,lfs) that use r2 as the source register - The branch instructions (

b,bl) that branch to functions after the executables diverge

Technically there could be more, but these are the ones present in the missing data.

I built a small program that reads a file containing PowerPC instructions, breaks them down into their constituent parts, and outputs a new file with the necessary adjustments. The r2-based load instructions proved easy to adjust since at least in this block, the change to the value of D is a constant 0x3E8.

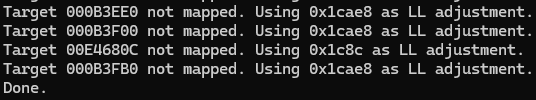

Branch instructions were harder to handle. I ended up having to build a map of branch target addresses with the change to LL required for the address to be correct in 3/17. Thunks aside, this worked quite well, and only one instruction in the sample data differed from the tool’s output (again because of thunking). If the function in question isn’t in the map, the tool just uses the value for whatever the one after it is (as long as the one before it is the same—otherwise it terminates).

After some trial and error, I got it working and even discovered that the missing 0x8000 from earlier was still on the image and was completely identical to the tool’s output. I was delighted about this and took it as confirmation that the tool had done its job. Then, only testing was needed.

End result

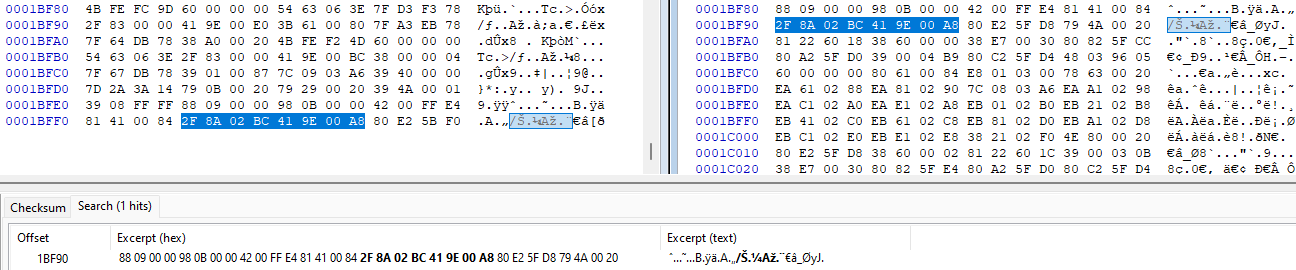

The executable was recreated from the following data:

| File offset | Length (bytes) | Disk offset |

|---|---|---|

| 0x0 | 0x1C000 | 0x40624A000 |

| 0x1C000 | 0x4000 | 0x41498A000 |

| 0x20000 | 0x10000 | Rebuilt |

| 0x30000 | 0x8000 | 0x40A2F2000 |

| 0x38000 | 0x10000 | Rebuilt |

| 0x48000 | 0x1FE8000 | 0x4149AE000 |

Which produced:

|

|---|

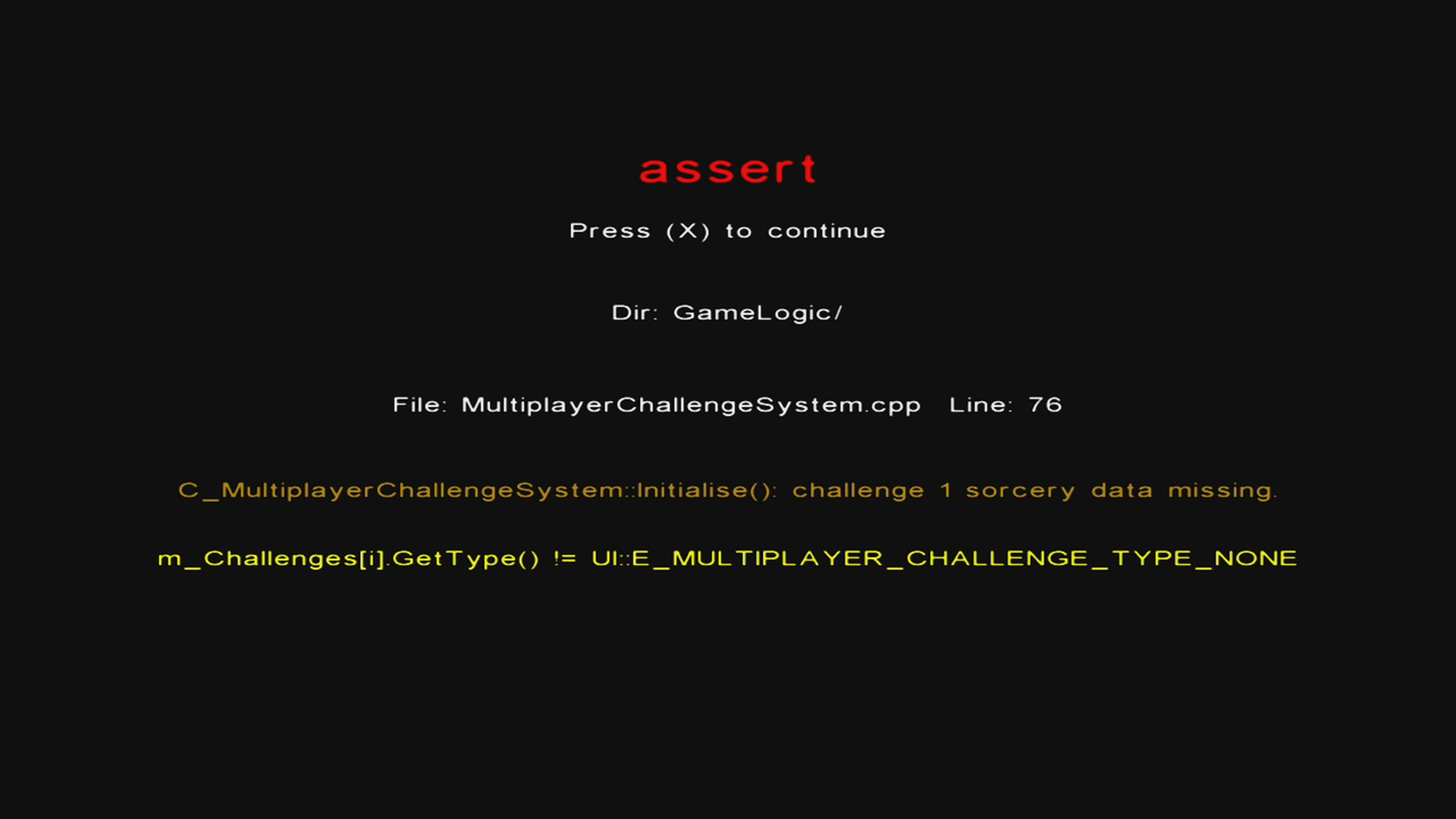

| Image credit: redlinesnative |

I was only able to get it to assert, but people in the Blur community ran it fine. Either way, the executable is clearly working perfectly, because if it wasn’t it would’ve died instantly rather than display anything. I know this because I messed it up a couple times and that’s what it did.

In any case, the recovered executable is available here.

There’s more that wasn’t discussed here but this post is already long enough. I’ll likely be putting this newfound knowledge and experience to use on recovering further Burnout Paradise executables, to the extent that it’s possible. Also, it’s my understanding that the .opd section contains the location of r2 for each function it lists, so perhaps that could have been used in the instruction-modifying tool but unfortunately I wasn’t able to find a way to correlate the changes listed in the generated map to the .opd changes. An idea for another time, perhaps.

If anyone actually read this, I hope you found it interesting, or at least liked the end result. Follow me on Bluesky and stuff.